The Give Me My Healthcare Taxes Back Act

A populist healthcare plan that establishes universal catastrophic coverage while giving the typical American family a $28,000/year raise

Executive summary

Healthcare middlemen take $32,000/year1 from the typical American family’s paychecks. They insert themselves into every healthcare purchase, big or small. What would healthcare look like if we eliminated 99% of the middlemen, limited insurance to big problems (heart attacks, car wrecks, etc.), and let Americans keep as much of the money they’ve earned as possible?

The Give Me My Healthcare Taxes Back Act is the answer. It’s a comprehensive overhaul of the US healthcare sector that creates the leanest, simplest, most straightforward healthcare system.

The Give Me My Healthcare Taxes Back Act (with its svelte acronym of GMMHTBA2) liberates American working families from paying $34,000/year3 in taxes and premiums to support employer-sponsored insurance ($1.3T/year), Medicare ($1T/year), Medicaid ($900B/year), and other miscellaneous government-created payers ($300B/year).4 It replaces those payers with a Fund for Health Crises (~$1T/year), leaving over $2T/year under the control of Americans who earned it.

As its name indicates, the Fund for Health Crises is a catastrophic payer that only covers health crises — heart attacks, car wrecks, cancer, and anything else that costs more than $10,000. It is not a high-deductible health plan; it is a health plan that only covers the really expensive things.

This makes health coverage work more like car insurance or homeowner’s insurance. Car insurance doesn’t cover an oil change or new tires, and homeowner’s insurance doesn’t cover a fresh coat of paint or a new roof. Likewise, under the GMMHTBA, the Fund for Health Crises doesn’t cover routine, everyday healthcare, and individuals purchase those goods and services directly from doctors and pharmacies using their own money.

With that simple framework, here’s what the GMMHTBA achieves:

It ensures reliable, uncomplicated, complete coverage for health crises;

It makes routine, everyday healthcare far less expensive and far more convenient/accessible; and

It eliminates 99% of the current healthcare bureaucracy.

This model reduces necessary healthcare taxation by a staggering $2T/year. The GMMHTBA allows the people who earned this money to keep it. The tax cuts/“raises” that result are astounding:

The typical American family gets a “raise” of $28,000/year;

The typical worker gets a “raise” of $11,000/year;

The typical individual worker without insurance gets a “raise” of $2,000/year; and

The typical retiree gets a financial boost of $9,000/year.

The GMMHTBA represents economic liberation for regular American working people and families. It means families can afford down payments. It means people can pay their bills. It means parents can send their kids to college. It means people can free themselves from debt. It means peace of mind that health crises won’t become financial crises.

Table of Contents:

Background: how the US healthcare system works now

How does the healthcare system work under the GMMHTBA)?

How does the GMMHTBA affect personal finances?

How does the GMMHTBA affect federal government finances?

How does the GMMHTBA affect the economy broadly?

What happens to the existing healthcare bureaucracy under the GMMHTBA?

What are the alternate forms of the GMMHTBA? How could it be modified?

Winners and losers under the GMMHTBA

Conclusion: economic liberation is within our reach

Background: how the US healthcare system works now

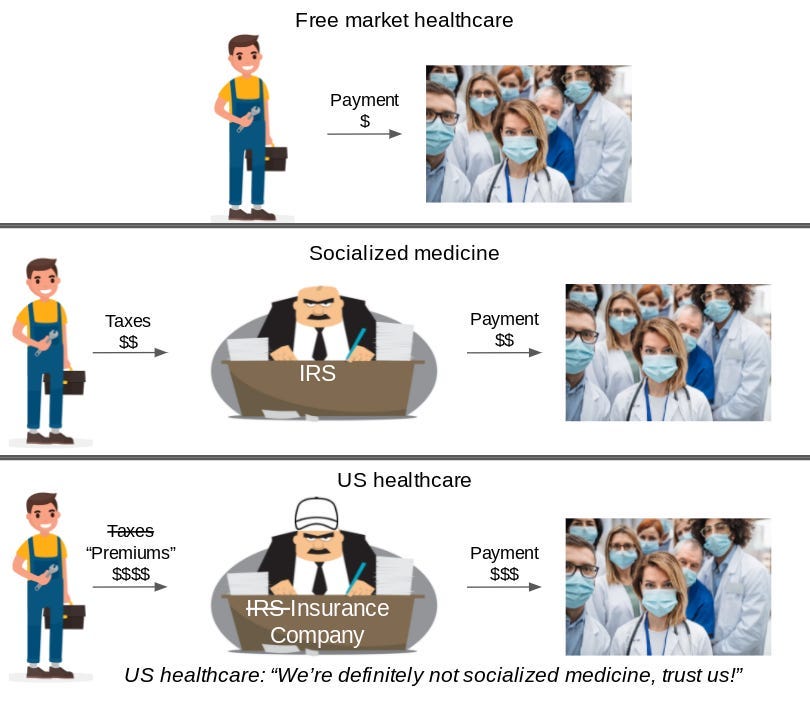

Healthcare in the United States currently works by taking money from people’s paychecks and using that money to pay for other people’s healthcare. In other countries that’s called socialized medicine, but in the US, we don’t call it that:

The US form of socialized medicine has a lot more bureaucrats than normal socialized medicine. We call these extra bureaucrats “insurance companies”:

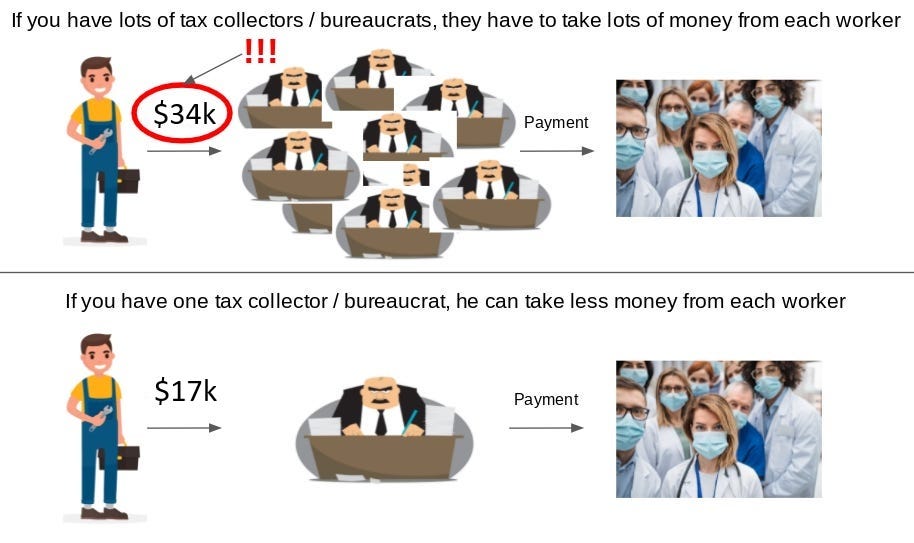

Because we have extra bureaucrats, we have to take a lot more money from people’s paychecks.5 The US takes $34,255/year in healthcare-related taxes and premiums (which are just taxes by another name6) from the median-income family. Other countries take half that:

If American families are being overcharged so much, why isn’t there more outrage? Because the bulk of the taxes and premiums are hidden from view. The American family thinks they’re paying $6,296 rather than $34,2557:

This is where the GMMHTBA enters the picture. The GMMHTBA acknowledges that having a middleman involved in routine, small healthcare purchases only makes them more expensive and less convenient. The GMMHTBA therefore eliminates the use of middlemen altogether for the vast majority of healthcare situations, like regular doctors’ visits, maintenance medications, and planned procedures. And, for situations that individuals can’t pay for themselves (car wrecks, cancer, etc.), the GMMHTBA has only a single middleman:

Let’s dig into how the healthcare system works under the GMMHTBA…

How does the healthcare system work under the Give Me My Healthcare Taxes Back Act (GMMHTBA)?

The GMMHTBA radically simplifies the healthcare system by radically simplifying the way that healthcare is paid for. Under the GMMHTBA, all healthcare is purchased in one of two ways:

For health crises, the Fund for Health Crises pays for it; or

For routine, everyday healthcare, individuals buy it directly with their own money.

Let’s address these individually.

Having the Fund for Health Crises pay for crises

In case of health emergencies and crises like a heart attack, a car wreck, or cancer, the Fund for Health Crises pays the providers.

Eligibility for the Fund for Health Crises is simple: all citizens, legal residents, and legal visitors7 are automatically covered. There is no application process.

An important question, of course, is what qualifies as a “health crisis” — i.e., what does the Fund for Health Crises cover? There are two categories of care covered by the Fund for Health Crises:

Emergency care; and

Conditions for which the cost of treatment in the market would exceed $10,000/year.

Here’s what falls under the second category (the “$10k/year” category):

Virtually all inpatient care;

Outpatient care and prescription medications for cancer;

Outpatient care and prescription medications for diabetes; and

Outpatient care and/or prescription medications for a long string of less-common but also serious and costly conditions.

The Fund for Health Crises spells out everything that qualifies on a public webpage in layperson-friendly language.

While the $10k/year limit seems arbitrary, it’s worth remembering that “what’s covered” is arbitrary under the current US healthcare system (and every other healthcare system), too. There’s no reason why prescriptions are covered and over-the-counter medications aren’t, and why physical therapists are covered but personal trainers aren’t. And having a single fund for catastrophic care is not a novel concept — Singapore’s Medishield Life is a similar concept.8

The healthcare industry argues that coverage of routine, everyday care (including preventative care) by financial middlemen is essential to accessing that care. However, the opposite is true — middlemen make routine, everyday healthcare less accessible and more expensive. The GMMHTBA makes routine, everyday healthcare more accessible and less expensive (as we’ll discuss in the next section).

The Fund for Health Crises is not a universal HDHP (high-deductible health plan). Under a HDHP, the third-party payer still intermediates transactions prior to the deductible phase of coverage. The Fund for Health Crises, on the other hand, is not involved in transactions for uncovered treatments at all.

Here’s how coverage under the Fund for Health Crises could be explained to the public:

The GMMHTBA gives you peace of mind about medical emergencies and crises.

Diagnosed with cancer? The Fund for Health Crises pays for all your treatment.

Get in a wreck? No need to worry about a bill from the ambulance or hospital.

There are no copays, coinsurance, or deductibles. There are no “allowable amounts,” “charges,” etc. There is no “we can’t tell you the price, ask your insurance company.” There is no “prior authorization.” There is no enrollment process. There are no “in-network providers” and “out-of-network providers.” There are no networks, period.

If you have an emergency or a big medical issue, you’re fully covered. It’s that simple.

Having a simplified Fund for Health Crises — rather than the millions of funds with millions of different rules we have today — pay for health crises improves healthcare in multiple ways:

Americans can be more confident that healthcare crises won’t result in extreme bills or bankruptcy.

When a health crisis arises, patients don’t need to think about the financial side of things.

Since the Fund for Health Crises has negotiating strength, it can pay hospitals reasonable prices instead of the ludicrous prices they’re currently paid. That means that the Fund for Health Crises needs to take less money from people’s paychecks to pay for care.

Hospitals don’t have myriad bureaucratic rules to comply with. That means their administrative costs decrease and they can focus on providing care.

Purchasing healthcare directly

A core tenet of the GMMHTBA is that healthcare is cheaper and more convenient when there’s no middleman involved. Under the GMMHTBA, individuals buy routine, everyday doctors visits and drugs with their own money.

To be clear, this means patients paying doctors and pharmacies directly, NOT patients paying their own third-party payer to then turn around and pay doctors and pharmacies for their care and other people’s care.

The GMMHTBA mandates that all providers list prices publicly. However, since the GMMHTBA eliminates third-party payment for most goods and services, this mandate is mostly superfluous. (Businesses that sell to consumers do not need to be told to display prices — they just do.) Additionally, the GMMHTBA forbids providers from charging a patient for anything without first disclosing the price.

Since Americans are so accustomed to everyday healthcare being complex and expensive, it’s difficult for them to accept that it can be simple and inexpensive. Regardless, here’s how it could be explained to the public:

Under the GMMHTBA, doctors and pharmacies advertise their prices, and if you want to buy their services or their stuff, you buy it.

It’s that simple.

Buying drugs becomes as simple as buying groceries. Buying a visit to a doctor becomes as simple as buying sessions from a trainer at the gym.

There are no copays, coinsurance, or deductibles. There are no “allowable amounts,” “charges,” etc. There is no “we can’t tell you the price, ask your insurance company.” There is no “prior authorization.” There is no enrollment process. There are no “in-network providers” and “out-of-network providers.” There are no networks, period.

“But you never know the price in advance in healthcare,” you might understandably worry. The GMMHTBA fixes that, mandating that doctors and pharmacies must post prices and forbidding doctors from charging for anything without informing you of the price in advance.

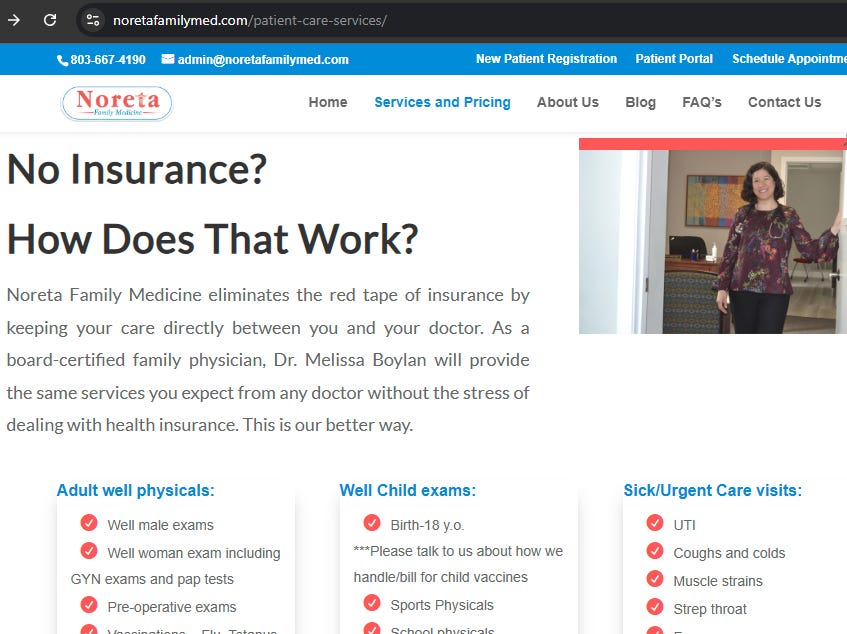

A small number of doctors and pharmacies already work this way. Let’s look at some examples.

If you wonder how easy it would be to schedule and pay for doctor visits under the GMMHTBA, look at sites like Sesame and imagine having hundreds of thousands of additional doctors available on them:

Or, look at “direct primary care” doctors (doctors that offer memberships with flat monthly fees). For example, a $70/month membership at Noreta (No Red Tape) Family Medicine includes in-person or telehealth visits at no cost and a number of additional services at no cost:

Even outpatient surgeries become affordable. See prices at the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, one of the few cash-pay surgery centers in operation today:

(Remember, complex inpatient surgery is covered under the Fund for Health Crises.)

If you wonder how easy it would be to purchase drugs under the GMMHTBA, see online cash-pay pharmacies like the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company:

…Or local brick-and-mortar pharmacies like Blueberry Pharmacy:

By getting rid of the unnecessary middlemen, healthcare becomes convenient and affordable. Look at the actual prices in the pictures above!

Having patients – rather than third-party bureaucrats theoretically acting on behalf of patients – purchase healthcare improves healthcare in five ways:

Doctors, drug companies, pharmacies, surgery centers and other healthcare providers can focus on delivering value for the patient instead of doing what gets them paid by third-party-payer bureaucrats. Services immediately become more customer-centric and convenient, like services in other industries.

Providers compete with each other on price, driving overall prices down.

Since higher-quality providers would be able to charge more, providers would strive to differentiate themselves based on quality, driving up quality. (In the current healthcare system, it’s difficult for providers to get paid more by doing a better job.)

All bureaucracy is eliminated overnight. Providers and patients alike are immediately liberated from the time-suck of dealing with paperwork, complexity, and billing.

Since prices are known, patients have less trepidation about purchasing healthcare. There’s no more “I don’t want to go to the doctor because I don’t know how much it’ll cost.”

In sum, routine healthcare becomes less expensive, more convenient, and higher quality.

How does the GMMHTBA affect personal finances?

As we saw in the previous section, the GMMHTBA creates immense value for the American public through its simplification of the healthcare system. However, its effect on personal finances is even more important.

The GMMHTBA’s over-arching economic principle is to let workers (and former workers) keep the money they’ve earned instead of giving it to healthcare bureaucrats. By following this simple principle, the GMMHTBA puts a total of $2.219T/year9 back into the pockets of the approximately 238M10 Americans who earned it.

Practically speaking, workers experience this as a raise – they have more money in their paychecks every week. However, since employers are already paying out this money (just to healthcare bureaucrats instead of the workers who earned it), these are raises that don’t cost employers anything.

On an individual level, the transformative impact of these raises is staggering: the typical working family gets a raise of $28,313/year, the typical worker with individual coverage gets a raise of $10,693/year, and the typical Medicare beneficiary gets a cash boost of $8,654/year.

These numbers seem impossible and shocking. But this is money people are already earning right now – it’s entirely possible to just let them keep it. And the numbers are only shocking because the public dramatically underestimates how much of their earnings are going to the healthcare system right now (see the “iceberg” pic from the background section).

The GMMHTBA achieves these “raises” by eliminating the primary ways that workers’ and former workers’ earnings have been artificially redirected to healthcare bureaucrats:

$1,286B/year of employee earnings that was previously redirected to healthcare bureaucrats for employer-sponsored insurance now goes directly to employees in cash;

$48B/year of military members’ Tricare benefits (roughly speaking, the military equivalent of employer-sponsored insurance) that was previously redirected to healthcare bureaucrats now goes directly to members of the military in cash;

$367B/year of employee earnings that was previously redirected to healthcare bureaucrats for the Medicare share of payroll taxes now goes directly to employees in cash;

$398B/year of Medicare benefits that was previously redirected to healthcare bureaucrats now goes directly to Medicare beneficiaries in cash; and

$120B/year of veterans’ benefits that was previously redirected to healthcare bureaucrats now goes directly to veterans in cash.

(Note: references and calculations for these and other figures can be found in this spreadsheet: Data and calculations for the GMMHTBA.)

Let’s see how this affects the personal finances of workers, Medicare beneficiaries, and members of the military.

Effect on workers’ personal finances

Under the GMMHTBA, workers receive raises through two mechanisms: the elimination of premiums for employer-sponsored insurance ($1.286T) and the elimination of the Medicare payroll tax ($367B). The first mechanism applies only to ~100M workers; the latter mechanism applies to all 170M people who worked at any point during the year.

Workers could find out exactly how much money they’d get back by looking at their W-2 form. The raise they’d receive from the return of their employer-sponsored health premiums is shown in Box 12 Code DD, and the raise they’d receive from the elimination of the Medicare payroll tax is in Box 6 of the W-2 multiplied by 2:

The first mechanism through which workers receive raises is the elimination of $1.286T in employer-sponsored insurance premiums. The amount of the raise each worker receives through this mechanism depends on the specific health plan offered by the employer and whether the worker has single coverage or family coverage.11 Remember, the GMMHTBA’s approach is to return to workers the money they’re already earning, and since workers are earning different benefits right now, it makes sense that the amount of money returned to workers would vary. Additionally, since approximately 70M workers do not participate in employer-sponsored insurance at all (due to coverage through their spouse or coverage not being offered by their employer), those workers do not receive a raise through this mechanism.

However, for the approximately 100M workers that do participate in employer-sponsored insurance, a worker with single coverage receives $8,951/year on average, and a worker with family coverage receives $25,572/year on average through this mechanism alone.

The second mechanism through which workers receive raises (in addition to the raise created by the elimination of employer-sponsored insurance) is the elimination of the $367B/year in Medicare payroll taxes collected every year. Since all 170M workers in America pay this 2.9% tax (which is also known as the Medicare portion of FICA), all 170M workers receive a raise through this mechanism. Through this mechanism, the typical family would receive a raise of $2,741/year, and the typical individual worker would receive a raise of $1,742/year.

Between the two mechanisms, the typical working family gets a raise of $28,313/year and the typical worker with individual coverage gets a raise of $10,693/year.

Again, to be clear, although employees receive massive raises, no employer spends any additional funds under the GMMHTBA, and there is no new governmental spending behind these raises. The employer simply takes the money it previously sent to healthcare bureaucrats (from employees’ earnings) and gives that money directly to the employees.

Effect on retirees’ (Medicare beneficiaries’) personal finances

Medicare beneficiaries paid into the Medicare program during their working years by paying the 2.9% Medicare payroll tax. Historically, those payroll tax payments have gone to bureaucrats at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services who then used those funds to spend $398B/year on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries.

The GMMHTBA simply gives Medicare beneficiaries the cash value of that benefit instead. The GMMHTBA distributes the $398B/year evenly12 across all 68M active Medicare beneficiaries for a cash payment of $5,846/year.

Additionally, Medicare beneficiaries currently pay $155B/year in premiums for Medicare Part B and Part D and $36B/year in Medigap premiums. Under the GMMHTBA, these premiums are no longer necessary. By eliminating the need for these premiums, the GMMHTBA saves the average Medicare beneficiary an additional $2,808/year. This is an average number; since different Medicare beneficiaries pay different premiums, the exact amount saved by a specific Medicare beneficiary under the GMMHTBA varies.

Between the $5,846/year in cash payments and the $2,808/year average savings from elimination of premiums, the typical Medicare beneficiary receives a cash boost of $8,654/year.

Again, it’s important to remember that these cash benefits are provided in addition to the complete coverage provided by the Fund for Health Crises. Retirees are fully protected in case of a health crisis.

Effect on military members’ personal finances

For Tricare and Veterans Affairs beneficiaries, the GMMHTBA authorizes the Defense Health Agency and the Department of Veterans Affairs to distribute their funds appropriately to their eligible members. They may consider years of service, disability status, or other criteria they deem appropriate; the GMMHTBA does not specify.

It is unlikely that an even distribution across all potentially eligible beneficiaries is the most appropriate approach. However, it’s instructive to look at the amounts that result from an even distribution to get a sense of the potential payments:

For Tricare participants, an even distribution of funds to all 9.4M Tricare beneficiaries would equate to a $5,103/year raise per beneficiary. Note that this amount is per beneficiary; a service member with multiple family members covered through Tricare would receive $5,103/year for each family member.

For veterans, an even distribution of funds to all 19M veterans would equate to a $6,295/year raise (a $19,184/year raise if distributed only to the 6.2M veterans who use VA services).

By giving military members and veterans cash benefits, it puts them on a level playing field with the general public instead of subjecting them to what has been sometimes criticized as subpar care.

Again, it’s important to remember that these cash benefits are provided in addition to the complete coverage provided by the Fund for Health Crises. Military members and veterans are fully protected in case of a health crisis.

Miscellaneous additional savings

In addition to the above effects, the GMMHTBA also eliminates the need for people who get their coverage through the ACA marketplaces to pay $24B/year in net premiums, and it eliminates the need for people who get coverage through the individual market to pay $27B/year in premiums.

And, since the Medicaid program is being abolished, states will no longer need to collect $280B/year in revenue to fund the state share of the Medicaid program. States could choose to lower their residents’ tax burden by $280B/year or maintain the same taxation level and fund new programs (including new Medicaid programs, if they’d like) on their own.

In sum, that’s an additional $331B/year or $51B/year (depending on whether states maintain their same income tax levels) back in Americans’ pockets every year.

Effect on out-of-pocket costs

Americans currently pay $505B/year in out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, copays, coinsurance, and direct cash purchases). Under the GMMHTBA, some of the $505B/year is covered by the Fund for Health Crises. However, for healthcare goods and services not covered by the Fund for Health Crises, consumers now pay the entire cost out-of-pocket.

Fortunately, cash-pay rates are already below rates paid by third-party payers — see examples from Sesame, the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, and others in the previous section in this article.

Additionally, having providers compete for customers’ business on price puts additional downward pressure on prices. The scale of this impact is hard to estimate, and would require further analysis. Americans will spend less than the $2.2T returned to them; exactly how much less they will spend is difficult to predict.

How does the GMMHTBA affect federal government finances?

The GMMHTBA drastically simplifies the complex governmental financing of healthcare. It eliminates a lot of different taxes, eliminates a lot of different spending, and creates one significant new source of spending (the Fund for Health Crises). Ultimately, the GMMHTBA reduces federal government spending by $323B/year and reduces federal government revenues by $34B/year, meaning it improves the federal budget by $287B/year.

Let’s walk through the individual effects on government finances step by step…

(Note: Citations and calculations for numbers in this section can be found under “Effects of the GMMHTBA on federal government finances” in this spreadsheet: Data and calculations for analysis of the GMMHTBA.)

Eliminated spending

The GMMHTBA eliminates three categories of federal government healthcare spending: $640B/year in Medicare spending (the Medicare spending above and beyond the $398B/year payroll taxes being returned to Medicare beneficiaries), $591B/year in Medicaid spending, and $91B/year in ACA subsidies. This is $1.323T/year in savings for the federal budget.

“Converted” spending

Additionally, the GMMHTBA converts spending on other federal health programs — Medicare ($398B/year), Veterans Affairs ($120B/year), Tricare ($48B/year), and FEHB ($44B/year) — into spending on cash payments to the beneficiaries of those programs. In one respect, the conversion of health benefits into cash is a budgetary non-factor: the federal government spends the exact same amount on cash payments as it did on those program benefits. However, there’s an important caveat: since these benefits are now taxable cash income, they generate tax revenues through income taxes and Social Security taxes. We’ll discuss that in the “New revenues” section below.

New spending

The new expenditure created by the GMMHTBA is, of course, the $1T/year Fund for Health Crises.

Current costs (across all payers, including out-of-pocket costs) for the categories of health spending covered by the Fund for Health Crises is approximately $1.219T/year, broken down as follows: $80B/year for emergency department care, $510B/year for inpatient care, $222B/year for cancer care, $306B/year on diabetes care, and a very roughly estimated $100B/year for the long string of less-common additional conditions whose treatment costs would exceed $10,000/year in the market. There is some overlap between these categories — some “cancer care” and “diabetes care” is also “inpatient care.”

The GMMHTBA reduces the cost of providing this care in two ways: 1) it eliminates administrative costs at providers and 2) it uses its monopsony power to negotiate better rates with providers (mostly hospitals). Crudely estimating the administrative savings to be $100B/year and the monopsony discount to be 25%, the total expenditures for the Fund for Health Crises could be estimated at $839B/year. Until a more thorough estimate has been performed, the GMMHTBA budgets for $1T/year.

Eliminated revenues

Under the GMMHTBA, the federal government no longer receives $367B/year in Medicare payroll taxes and $155B/year in premiums from Medicare beneficiaries, a sum of $522B/year in eliminated revenues.

New revenues

The GMMHTBA does not create any new taxes. However, it significantly increases the tax base by returning $2.218T/year in cash to workers and retirees. This generates new income tax revenue and new Social Security tax revenue.

The exact value of the increase in tax revenue is hard to predict – it depends on the specific income levels of the individuals receiving the cash payments. However, we can make an informed estimate. Treating the $1.286T/year in employer-sponsored insurance premiums as taxable income is estimated by the Joint Committee on Taxation to generate an additional $213B/year in income tax revenue and approximately $70B/year in Social Security tax revenue.

Extrapolating those numbers to the entire $2.249T/year being returned to workers and former workers as cash benefits implies the production of $368B/year in new federal income tax revenue and $120B/year in new Social Security payroll tax revenue for a total of $488B/year in new revenue.

Total impact

Overall, the GMMHTBA eliminates $1.323T/year in spending, adds $1T/year in spending, eliminates $522B/year in revenue, and adds $488B/year in new revenue. On net, the federal budget improves by $288B/year.

How does the GMMHTBA affect the economy broadly?

What impact would the GMMHTBA have on macroeconomic issues – employment, poverty, inflation, etc.? It’s an important question – the current healthcare system creates trillions of dollars of distortion in the US economy. By removing these distortions, the GMMHTBA creates significant shifts in the economy.

Effects on labor and employment

The GMMHTBA has several effects on labor and employment:

By eliminating employer-sponsored insurance and the Medicare payroll tax, the GMMHTBA makes American labor significantly cheaper relative to offshore labor, shifting jobs back to the US. Although employers must continue to pay the current value of current employees’ health premiums and Medicare payroll taxes to those employees, the GMMHTBA places no such restriction on new workers. While the cost of offshore labor remains the same, it takes less total compensation to achieve the same take-home pay as it did prior to the GMMHTBA.

By the same mechanism, the GMMHTBA makes labor less expensive relative to capital.

Since a worker’s healthcare is no longer tied to their specific job, the GMMHTBA enables workers to change jobs more easily.

Since the loss of employer-sponsored insurance is no longer a concern, the GMMHTBA enables more Americans to become small business owners and entrepreneurs.

On the other hand, the GMMHTBA eliminates approximately 2.7M existing bureaucratic/administrative jobs (see the “What happens to the existing healthcare bureaucracy under the GMMHTBA” section below). While the GMMHTBA increases employment broadly, it will take time for these 2.7M workers to reintegrate into the workforce, and they will compete with certain subsets of the existing 170M-person workforce, exerting a downward pressure on wages for those subsets.

Effects on inequality

The GMMHTBA affects inequality in two ways:

Since premiums for employer-sponsored insurance are generally not calculated as a percent of income, the GMMHTBA significantly reduces inequality among workers with employer-sponsored insurance. In other words, health premiums have historically consumed a greater percent of the income of middle-income workers than that of the upper-income workers, and by doing away with these premiums, the GMMHTBA reduces inequality between middle-income workers and upper-income workers.

The GMMHTBA’s effect on inequality with respect to low-income individuals depends on whether some portion of the earnings being returned to workers is directed towards low-income individuals (see the “Using some of the savings to eliminate poverty” section below). Without redirecting some portion of the funds, the GMMHTBA further increases gap between low-income individuals and middle-income individuals. With a poverty-elimination amendment, the GMMHTBA could significantly decrease the gap.

Effects on business productivity and competition

The GMMHTBA has two effects on business productivity and competition:

Since big businesses were previously able to provide healthcare benefits more efficiently than small businesses, the GMMHTBA eliminates an advantage that big businesses had over small businesses, leveling the playing field.

By eliminating businesses’ burden to purchase healthcare for their employees, the GMMHTBA increases overall corporate productivity by lowering HR expenses and removing a distraction. Hiring across state lines becomes less of a headache for businesses.

Effect on overall consumption and investment

It’s difficult to predict how individuals will spend, save, and invest the $2.2T/year in earnings that the GMMHTBA restores to them. Of course, some portion of that will be spent on direct purchasing of healthcare services — perhaps $750B/year. But it certainly won’t be the entire $2.2T/year. The decreased consumption within the healthcare sector becomes additional savings, investment, and consumption in other sectors ($1.45T/year, if the $750B/year estimate is correct). That’s great news for all non-healthcare sectors of the economy.

Effect on investment in the healthcare sector

Since the GMMHTBA shifts financial control from third-party payers to price-conscious consumers, investment in healthcare likely goes down overall. However, it also becomes more productive — investment changes from “making things that can get reimbursed by bureaucrats” to “making things to create value for individuals.” In other words, there is likely less investment in “me-too” drugs (no more endless tv ads for plaque psoriasis drugs) and more investment in technology to make services more convenient.

Effect on inflation

Under the GMMHTBA, no new money is printed. By removing the massive subsidies for the healthcare industry and having the majority of the industry function like a normal market, the GMMHTBA will cause price levels to fall in the healthcare sector. However, by restoring income to workers, it pushes up prices in other sectors.

Overall impact on the economy

In sum, the GMMHTBA eliminates a massive drag on the US economy, killing off what Warren Buffet describes as a “tapeworm” on our economy.

The scale of the GMMHTBA’s economic effects might seem scary. But remember that the GMMHTBA isn’t doing any special with the healthcare sector; it’s just making the healthcare sector normal. Since the US healthcare sector is so thoroughly abnormal right now, making it normal is a big change, but it isn’t one we need to be scared of.

The GMMHTBA creates no economic distortions; it only removes them. By removing the massive economic distortions caused by the US’s extreme and bizarre healthcare system, the GMMHTBA creates a stronger, more vibrant economy.

What happens to the existing healthcare bureaucracy under the GMMHTBA?

The GMMHTBA is incredibly beneficial for the vast majority of Americans, but it is clearly detrimental for one group: healthcare bureaucrats. It eliminates approximately 2,000 federal programs/plans for paying for healthcare, approximately 2.5M different employer-sponsored insurance health plans, and approximately 2.7M bureaucratic/administrative jobs.

Government programs and plans eliminated by the GMMHTBA

With respect to government programs and plans, the GMMHTBA eliminates 1,978 federal healthcare administration programs and plans:

Medicare Part A

Medicare Part B

All 982 Part C (Medicare Advantage) plans13

All 464 Medicare Part D plans14

All 56 Medicaid agencies15

All 282 Medicaid MCOs16

All 180 Federal Employee Health Benefits plans17

All 11 Tricare plans18

The healthcare portions of the Veterans Administration

Government-created programs and plans eliminated by the GMMHTBA

When it comes to bureaucracy, the explicitly governmental programs/plans are only the tip of the iceberg. The larger bureaucracy exists in the employer-sponsored insurance plans, which were created from the tax benefits enacted in WWII and enshrined by the Revenue Act of 1978. These plans are administered by UnitedHealth, BCBS, Cigna, Aetna, and many more. Although these are private corporations, they are products of government legislation and regulation, and would not exist without the government legislation and regulation that created them.

The GMMHTBA repeals the legislation that created these companies, and under the GMMHTBA, they cease to exist. The net result is the elimination of two-and-a-half million19 employer-sponsored “plans” (i.e., ways to pay doctors, hospitals, and pharmacies), a staggering elimination of bureaucracy.

Jobs eliminated by the GMMHTBA

In eliminating the above organizations, the GMMHTBA eliminates approximately 2.7M bureaucratic/administrative roles.20 These are jobs that are creating no real economic value. However, they are jobs nonetheless. The GMMHTBA is clearly detrimental to people in those roles, and people in these roles have an incentive to oppose the GMMHTBA as strongly as possible.

What exactly are these 2.7M jobs? The most obvious category is the employees of the insurance companies themselves – approximately 800,000. But providers employ an estimated 1,600,000 administrative staff to battle the middlemen. And then there’s a long tail of professionals that feed off the complexity of healthcare reimbursement: consultants, attorneys, finance professionals, policy analysts, billing companies, healthcare software companies, etc. The GMMHTBA provides a job retraining benefit for these workers.

While 2.7M seems like a large number, it’s worth remembering that these 2.7M jobs are costing the other ~160M Americans workers (and 68M retirees) $2.2T/year. The American economy is objectively weaker because these 2.7M jobs exist.

It’s also worth remembering what the GMMHTBA does not eliminate. The GMMHTBA does not eliminate the roles of any actual healthcare providers (doctors, nurses, pharmacists) who create real value for patients.

What are the alternate forms of the GMMHTBA? How could it be modified?

There are a couple natural, obvious ways to modify the GMMHTBA while keeping its core philosophy of “eliminate as much of the healthcare bureaucracy as possible and let people buy stuff directly” intact.

Using some of the savings to eliminate poverty

Since the 79M Medicaid beneficiaries haven’t “earned” the $872B/year sent to health care bureaucrats to spend on their behalf, the GMMHTBA — in its current form — doesn’t return that money to them.

It’s possible to create a version of the GMMHTBA that still massively benefits workers while also benefiting low-income individuals. Instead of returning $1,701B/year to workers, the GMMHTBA could be modified to return $1,301B/year, and the remaining $400B/year21 could be used to eliminate poverty.

That would equate to a $5,044/year payment per Medicaid beneficiary. And since 47% of Medicaid beneficiaries are children22 and 60% of adult Medicaid beneficiaries are female,23 it’s more realistic to envision this benefit as $10,088/year per mother and child on Medicaid.

The GMMHTBA already provides Medicaid beneficiaries catastrophic coverage through the Fund for Health Crises. With this poverty-eliminatinon modification, it could enable them to participate in the simplified cash-pay market for their non-critical health needs AND provide them economic security.

This $400B/year in aid to low-income individuals would immediately dwarf the largest existing benefit for low-income individuals ($113B/year in SNAP spending), becoming the most meaningful poverty reduction program in American history.

Eliminating legislation and regulation restricting the supply of healthcare

The GMMHTBA focuses on the biggest economic problem with healthcare: the way we pay for the goods and services provided to us. It does not address artificial restrictions on the ability to provide those goods and services: limitations on the practice of medicine, certificate of need laws, prescription requirements (as opposed to making drugs available over the counter).

It would be natural to combine the GMMHTBA with legislation eliminating these restrictions. In the same way that GMMHTBA allows people to do what they want with their own money, such “freedom to practice/sell” would enable providers and businesses the freedom to appeal to customers without restriction.

Returning to Medicare beneficiaries the exact amount they contributed to Medicare

As discussed in footnote 12 (from the section on the financial impact on Medicare beneficiaries), the GMMHTBA could be structured to return to Medicare beneficiaries the exact amount of money they contributed to Medicare through their working years. The GMMHTBA is structured as it is (distributing funds equally among all Medicare members) because the data to accurately estimate the cost of refunding the exact amount of money they contributed is not readily available.

Expanding or contracting the scope of the Fund for Health Crises

The GMMHTBA could easily be modified to have the Fund for Health Crises cover more services or fewer services. “What’s covered” is an arbitrary decision under the existing US healthcare system, as it is under any other country’s healthcare system.

Winners and losers under the GMMHTBA

At the highest level, the biggest winner of the GMMHTBA is the general public, and the biggest loser is the healthcare bureaucracy — UnitedHealth, BCBS, etc. But it’s worthwhile to dig into the details of how the GMMHTBA affects different groups:

Winners

Patients

The patient experiences improves drastically. Now that patients have the dollars, healthcare providers becomes patient-centric, striving to provide convenience and value to patients.

Patients have peace of mind about healthcare costs — coverage under the Fund for Health Crises is automatic, and the payment is complete. Cash-pay costs are clear, and there are no surprises.

Workers

Workers who have employer-sponsored insurance immediately get $9,000-$26,000 raises.

Additionally, all workers (whether or not they have employer-sponsored insurance) immediately get 2.9% raises from the elimination of the Medicare payroll tax.

All workers can change jobs more easily; demand for onshore workers increases relative to offshore workers; labor becomes less expensive compared to capital.

The best doctors (and other medical practitioners) and the best drugs

Under GMMHTBA, the best doctors and the best drugs rise to the top. Under the current health system, the best doctors and best drugs can’t command higher rates than less effective doctors and drugs.

Doctors (and other medical practitioners) in general

No more hassle from dealing with endless documentation due to the complexity of the payer system.

Low-income individuals (if the poverty-reduction amendment is added to the GMMHTBA)

With the poverty-reduction amendment to the GMMHTBA, low-income individuals’ financial concerns would be directly addressed. Putting cash into their hands meets their needs more effectively than Medicaid, which enables low-income individuals to put cash into the healthcare industry’s hands.

Losers

Healthcare bureaucrats

As stated before, the biggest loser from the GMMHTBA is the ~2.7M healthcare bureaucrats who lose their jobs.

Underperforming doctors (and other medical practitioners) and drugs

The existing healthcare system doesn’t compensate underperforming doctors and drugs less than high-performing doctors and drugs. Putting dollars back into the hands of patients means that patients won’t be willing to pay as much for poor service or for drugs that don’t make much of of a difference.

Low-income individuals (if the poverty-reduction amendment is not added to the GMMHTBA)

Without amending the GMMHTBA to replace the Medicaid benefit with some form of cash benefit, Medicaid beneficiaries would lose benefits (even if the value of those benefits was questionable). Regardless, they would still have coverage under the Fund for Health Crises.

Conclusion

Economic liberation is within our reach

At first glance, the scope of changes made by the GMMHTBA may seem extreme and even frightening. But the GMMHTBA system boils down to something quite simple and normal: letting people buy inexpensive stuff with their own money and having a simple streamlined payer for expensive stuff.

There’s nothing extreme about that. What’s actually extreme is the totally unnecessary complexity of our current hodgepodge of bureaucracy — millions of superfluous bureaucrats taking trillions of dollars from American workers. By doing away with all the complexity, the GMMHTBA makes healthcare normal.

Additionally, the raises offered by the GMMHTBA seem simply impossible at first glance. It seems like it can’t possibly be feasible to give the vast majority of Americans $9k-$28k/year raises AND provide universal coverage without printing money. But that’s a testament to just how much waste there is in the existing US healthcare system. The dollars are all already there.

In terms of the economic burden its healthcare industry places on its citizens, the United States ranks 195th out of 195 countries. That’s a sobering statistic, but it also shows that fixing healthcare is far-and-away the most meaningful policy opportunity in America. In other words, healthcare is where we have the biggest room for improvement. No policy change comes anywhere close to providing the GMMHTBA’s ~$10k/year boost to every adult American.

As much of a boon as the GMMHTBA would be to the vast majority of Americans, it won’t come easily. Politically, the GMMHTBA pits 2.7M bureaucrats (and others in the healthcare industry who financially benefit from the bureaucracy) against the rest of America – all 340M of us. The healthcare bureaucracy is very wealthy and very influential, and they will oppose the GMMHTBA with all their might.

However, if we’re willing to accept this battle against the healthcare bureaucracy, economic liberation is ready and waiting for regular Americans.

See this article. The $32,000 is based on a median-income family of four with average employer-sponsored insurance premiums.

The point of the name Give Me My Healthcare Taxes Back is to communicate that the Act is restoring income to those who have earned it. Perhaps another name is more appropriate, though? Perhaps the more salient effect of the Act is that it’s eliminating the healthcare bureaucracy, and the Eliminate the Healthcare Bureaucracy Act, the End the Healthcare Middlemen Act, or the Simplify American Healthcare Act is a better name. Or, since it’s restoring individual choice in healthcare, perhaps the Restore Healthcare Freedom Act (or even the Make America Healthy Again Act).

You’ll note references to both “$34,000” and “$32,000” in this article — that is not a typo. The “$32,000” figure refers to income-related taxes and premiums, while the “$34,000” figure refers to all taxes (including things like sales tax and property tax) and premiums. See this article and this spreadsheet for the calculations of these numbers.

Components include Veterans Affairs ($120B), the ACA Marketplace ($115B), DoD/Tricare ($48B), Medigap ($36B). This adds up to $319B; I round down to simplify the math.

This is partially because the extra bureaucrats themselves are costly (and because providers must employ extra staff to deal with the bureaucracy), and partially because a fragmented bureaucracy has less negotiating strength than a consolidated bureaucracy.

Let’s briefly recap why “premiums” are economically and functionally equivalent to taxes: Like taxes, healthcare premiums are money taken from your paychecks and used to pay for other people’s stuff. And although they aren’t technically compulsory, practically speaking, they are: 1) as an employee, if you opt out, you only get $6,296 back, not $25,572; 2) the $6,296 you receive for opting out is taxed whereas the health premium is not; and 3) since US providers are oriented towards third-party payment, it’s the only way to access goods and services in the healthcare sector right now.

Under the current version of the GMMHTBA, the Fund for Health Crises does not provide coverage for illegal immigrants.

Singapore’s MediShield Life is similar, but not identical. MediShield Life imposes cost-sharing requirements.

For this and other data points and calculations, see Data and calculations for analysis of the GMMHTBA.

The sum of workers and Medicare beneficiaries.

This illuminates a bizarre side effect of the current employer-sponsored insurance system: workers with families effectively cost employers more than single workers. Over time, as contracts get renegotiated, compensation for single workers and workers with families will likely converge.

Ideally, the GMMHTBA would return to every American the exact amount they (and their employers) have paid into Medicare through payroll taxes – plus appropriate interest – once they reach retirement age. The payments would be made through an addition to the Social Security benefit. Each American can see the exact amount they and their employers have paid in Medicare taxes over the years by looking at the “Medicare taxes” figure at the bottom of Page 2 of their Social Security Statement, available for download at SSA.gov. This would be the amount that would be returned to them over time. For a typical new Medicare beneficiary, it would be approximately $107,000. However, data showing the amount of money paid by each specific worker minus the amount paid out in benefits on behalf of each living Medicare beneficiary is not publicly available, making it difficult to get an estimate of the cost of this benefit. The amount paid would vary significantly by beneficiary, and well-compensated individuals would get paid more, turning the payout regressive unless a cap were placed on the payouts.

https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-advantagepart-d-contract-and-enrollment-data/ma-plan-directory

https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-part-d-in-2025-a-first-look-at-prescription-drug-plan-availability-premiums-and-cost-sharing/

Since Medicaid is funded by both the federal government and the states (it varies by state, but the split is roughly 70/30 on the whole), state governments could theoretically continue running these programs if they’re willing to assume the federal portion for the program.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mcos/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

https://www.opm.gov/healthcare-insurance/carriers/fehb/

https://tricare.mil/Plans/HealthPlans

https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/researchers/statistics/retirement-bulletins/annual-report-on-self-insured-group-health-plans-2023.pdf

See https://peri.umass.edu/images/publication/Medicare-For-All-12-5-18.pdf. The UMass study does not include estimates for the long tail of outside professionals whose employment is derived from existing bureaucratic processes eliminated by the GMMHTBA — the GMMHTBA estimates there to be approximately 300,000 such roles.

For administrative simplicity’s sake, this $400B/year should be raised through tax mechanisms that are not eliminated by the GMMHTBA (income tax, tariffs, etc.) rather than keeping the special taxes that the GMMHTBA eliminates (employer-sponsored insurance, Medicare payroll tax) in existence.

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html#:~:text=37%2C616%2C104%20people%20were%20enrolled%20in,Medicaid%20and%20CHIP%20program%20enrollment

https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/medicaid-coverage-for-women/