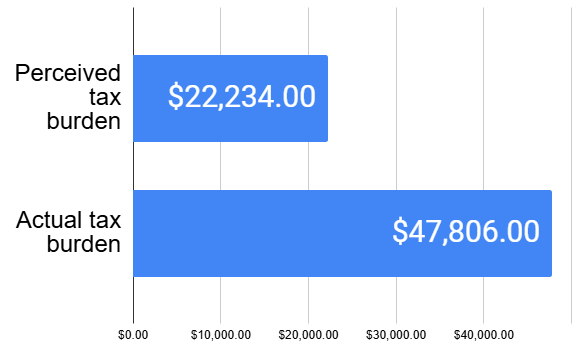

The tax burden for a median-income American family is twice what it's perceived to be

Bureaucrats take $47,806 from the typical American family's paychecks every year, but only $22,234 is considered "taxes"

Some “common knowledge”:

Europe has high taxes, America has low taxes.

America has a progressive income tax system, so tax rates increase with income.

The problem with this “common knowledge” is that it’s true only in a technical sense.

In a practical sense, the opposite is true: America has very high taxes, and they’re regressive.

The reason for the disconnect is this: the largest chunk of money ($25,572, on average) taken from the labor income of the typical median-income American family and spent on other people is labeled a “health premium” rather than a “tax.” And that premium isn’t calculated as a percent of income, so it acts as a regressive tax.

This disconnect between technical tax rates and practical tax rates causes a host of problems in politics and policy.

Why health premiums are economically and functionally equivalent to taxes

Premiums - like income/payroll taxes - are funds extracted from labor income by an administrator and used to pay for other people’s stuff.

From an economic perspective, it doesn’t matter whether the the administrator extracting the funds is BCBS or the IRS. Either way, the employee loses control of the funds that the employer has allocated for their employment. Either way, the employee retains less of their earnings.

A quick thought experiment: if Canada (or any other country) replaced its health payer system with BCBS, and continued to fund the payer with the same taxes, but called the taxes “premiums,” would that mean the country’s taxpayers immediately experienced a huge tax cut? Of course not. But in the US, we consider our taxes to be lower for this very reason.

“But taxes are compulsory, and participating in health coverage isn’t,” you might object. But because of the regulatory framework created for healthcare, healthcare premiums are practically compulsory:

If an employee declines health coverage, they don’t receive the full premium paid to them in cash - they only receive the “employee share.” For the average worker with family coverage, the employee share is only $6,296 of the total $25,572 premium.1

If the employee chooses to receive the $6,296 as cash, both the employee and the employer will be taxed on the payment. (The employee will have to pay state income taxes, federal income taxes, and payroll taxes; the employer will have to pay payroll taxes.) So that leaves the employee with roughly $4,000.

The US healthcare system is engineered towards third-party payment, so it’s challenging to purchase health services without participating in the system.

So while there isn’t technically a legal mandate to participate in employer-sponsored coverage, the legislative and regulatory framework heavily, heavily penalizes non-participation, making it practically compulsory.

Americans’ actual tax burden

If we agree that premiums function as taxes, here’s the high-level view of the actual tax burden for a median-income family of four based in Des Moines, Iowa2:

(Full calculations here.)

Simply including premiums increases taxes from $22,234 (17% of total comp)3 to $47,806 (38% of total comp)! Obviously, that isn’t a trivial difference.

Unfortunately, virtually all policy and academic analyses are based on the former number, not the latter, despite the latter being more comprehensive and more meaningful.

We can extend the analysis to include non-income-related taxes like sales taxes, fuel taxes, and property taxes. These are probably less relevant for the purposes of this discussion, but for the record, here they are:

By including premiums in our calculation of taxes, we also see the degree to which the the typical middle-income family’s4 taxes go to health industry: for every $100 taken from their paychecks, $67 goes to the healthcare industry. Yes, you read that correctly; for the typical middle-class American family, two thirds of their income-related taxes ($32,242 out of $47,806) go to healthcare.

Think tanks and policy analysts focus strictly on the technical tax burden rather than the practical tax burden

You’d think enterprising think tanks, policy analysts, and academics would want to point out the tax-like nature of premiums and incorporate them into their analyses, but aside from Gabriel Zucman, virtually none of them do.

Look at the discussion of individual tax rates:

The Peterson Foundation: “All income groups pay taxes, but overall the U.S. federal tax system is progressive.” “In the aggregate, our federal tax system is structured to be generally progressive, with higher-income taxpayers paying a larger share of their income in taxes.”

Economic Policy Institute: “Taken as a whole, the federal tax system is progressive—people with higher incomes tend to face higher tax rates.”

The Pew Research Center: “Among developed nations, Americans’ tax bills are below average.”

The Tax Foundation: “The U.S. has a progressive income tax system that taxes higher-income individuals more heavily than lower-income individuals.”

The Tax Foundation (again): “Yes, the US Tax Code Is Progressive”

The Heritage Foundation: “[T]he rich already pay a disproportionate share of federal taxes.”

CBO’s resources on tax rates include no mention of health premiums.

And look at the discussion of taxes as an overall percentage of GDP:

The Tax Policy Center (Brookings / Urban Institute): “US taxes are low relative to those in other high-income countries.”

Economic Policy Institute: “The United States taxes a lot less, and spends a lot less, than almost every other rich country.”

OECD’s comparisons of tax rates exclude health premiums.

Media follows the lead of policy analysts, academics, and think tanks, repeating the same message:

The New York Times: “In general, income taxes are progressive, meaning that Americans with more income pay a higher tax rate.”

CBS: “about 6 in 10 mistakenly believe middle-income households shoulder the highest tax burden.”

The Balance: “It might come as a surprise to some, but the United States is actually on the bottom end of the tax scale when compared to other nations.”

The accuracy of all of the above quotes is fully dependent on their omission of health premiums. Without the omission of premiums, taxes in the US flip from “low and progressive” to “high and regressive.”

Misunderstanding practical tax rates causes a host of political/policy problems

In an era of political polarization, misunderstanding Americans’ tax burden is unfortunately a bipartisan practice:

Because of health premiums, Americans’ practical tax burden is as high as socialist Scandinavian companies, but I’ve never heard a single Republican say that! Republicans should be outraged at how high the practical tax rate is.

On the Democratic side, the flat nature of the premium (“the secretary pays as much as the CEO”) makes the overall tax structure regressive - where is the Democratic outrage about this?

Our collective whiff on this issue creates a host of problems:

Most discussions of income taxes don’t mention healthcare at all, despite two thirds of income-related taxes going to healthcare.

There’s little understanding that healthcare taxes are the #1 economic issue for the American middle class.

The general public perceives our healthcare industry to be less “government-run” than it is.

Neither party is trying to meaningfully lower taxes on the middle class because there’s no understanding of what those taxes actually are.

Additionally, there are second-order effects. “How much we tax labor” is an important input for many analyses of economic issues (for example, the drivers of inequality, onshoring vs offshoring incentives, etc.). Without a holistic picture of Americans’ labor-related taxes, these analyses are based on inaccurate/incomplete inputs.

Moving forward

Fortunately, it’s possible to treat healthcare premiums as taxes moving forward. Healthcare and taxes are both very complicated topics, and some analyses would be easier to update than others. But to have an accurate, holistic understanding of Americans’ tax situation, it’s necessary. Think tanks and academics can do this.

At the very least, adding disclaimers would not be difficult: “This analysis does not include health premiums, which constitute the largest amount of money taken from labor income for middle-income families.”

Let’s move towards a more accurate, more holistic understanding of taxation - and healthcare - in America.

There are state-level regs establishing minimum employer contributions, but in general, “Most states generally require that companies contribute to at least 50 percent of employee premiums.” For example, in Hawaii, “For single coverage, your employer must pay at least one-half the premium cost.”

I chose Iowa because its state income tax seemed close to the median.

With respect to the “17%” number, there are a million different ways to calculate “tax rates” (with respect to both the numerator and the denominator). For example, are the employer’s share of payroll taxes included? Are unemployment taxes included? And are we referring to the marginal tax rate or the effective tax rate? Are 401k matches included in total comp? Because of this, you see lots of different numbers for typical tax rates or tax wedges. The takeaway is NOT that “17% is the authoritative median tax rate.” The takeaway is that NONE of the tax rates you see in published reports (whether from government sources or private sources) incorporate the $25,572 in health premiums.

In this article, I use “family” rather than “individual worker” as the unit of analysis. Since the ratio of family premiums to individual premiums is higher than the ratio of family income to individual income, the discrepancy between technical taxes and practical taxes is more pronounced with families than individual workers (although it’s still very pronounced for individual workers!). I’ll create another analysis based on an individual worker if time permits.